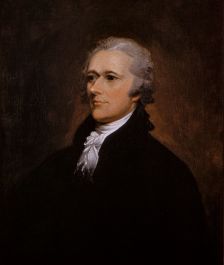

One in a series on Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow. On July 18, we discussed his views on central government vs. states’ rights:

https://billcornishwordpresscom.wordpress.com/2017/07/18/hamilton-early-lessons-still-apply/

Today, we see his views on religion.

At the end of his life, Hamilton sought out a religious experience more deeply than he did earlier on. As he lay dying after Aaron Burr shot him in a duel, “he made it a matter of urgent concern to receive last rites from the Episcopal Church.” (p. 706)

Hamilton asked for the Rev. Benjamin Moore, rector of Trinity Church in New York City and the Episcopal bishop of New York. Moore balked at giving Hamilton holy communion for two reasons: “He thought dueling an impious practice and did not wish to sanction the confrontation with Burr. He also knew that Hamilton had not been a regular churchgoer.” (p. 707)

Hamilton then turned to a close friend, the Rev. John M. Mason, pastor of Scotch Presbyterian Church, near Hamilton’s home in New York City. Mason said he could not administer communion to Hamilton because “it is a principle in our churches never to administer the Lord’s Supper privately to any person under any circumstances.” (p. 707)

Hamilton then returned to Moore. Hamilton’s friends pressured the bishop to grant the dying man’s last wish. Moore eventually agreed, and gave holy communion to Hamilton. (p. 708)

Hamilton repeated to Bishop Moore that he bore no malice toward Burr, that he was dying in a peaceful state, and that he was reconciled to his God and his fate. (p. 708)

While he professed faith throughout his life, it wasn’t a deep-seated tenet of everything he said and did.

Like Adams, Franklin and Jefferson, Hamilton had probably fallen under the sway of deism, which sought to substitute reason for revelation and dropped the notion of an active God who intervened in human affairs. At the same time, he never doubted God’s existence, embracing Christianity as a system of morality and cosmic justice. (p. 205)

Deism, according to an online dictionary, is “belief in the existence of a supreme being, specifically of a creator who does not intervene in the universe. The term is used chiefly of an intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries that accepted the existence of a creator on the basis of reason but rejected belief in a supernatural deity who interacts with humankind.”

I see a similar thread across the United States today. According to Gallup, 89 percent of Americans say they believe in God, although that number is declining. http://www.gallup.com/poll/193271/americans-believe-god.aspx At the same time, also according to Gallup, 75 percent of Americans identify as Christian, a number that also is declining. http://www.gallup.com/poll/187955/percentage-christians-drifting-down-high.aspx

A vast majority of us today believe in God’s existence, as Hamilton did. Do we believe He intervenes in human affairs? Many say yes but wish He wouldn’t, saying things, for example, like: Why do bad things happen to good people?

Hamilton, however, believed in an impersonal God who just lets life happen. He saw the Bible “as a system of morality and cosmic justice” that transcends humankind.

For Hamilton, the French Revolution had become a compendium of heretical doctrines, including the notion that morality could exist without religion … (p. 463)

Yet for most of his life, religion could go only so far, in his view.

Like other founders and thinkers of the Enlightenment, (Hamilton) was disturbed by religious fanaticism and tended to associate organized religion with superstition. … Like Washington, he never talked about Christ and took refuge in vague references to “providence” or “heaven.” (p. 659)

His wife, Eliza, on the other hand, had a very strong Christian faith throughout her life. She rented a pew at Trinity Church, “increasingly spoke the language of evangelical Christianity,” (p. 659) and likely would not have married a man who did not share her faith to some degree (p. 660).

(Eliza) was a woman of towering strength and integrity who consecrated much of her extended widowhood to serving widows, orphans and poor children. (p. 728)

Alexander Hamilton also doted on his children – he and Eliza had eight – when he had the time, which wasn’t often because of his extremely busy public life. And he and Eliza off and on also hosted orphans and other non-family members in their home, a sensitivity that Alexander had because he was an orphan while growing up in the West Indies.

But Alexander Hamilton “lived in a world of moral absolutes and was not especially prone to compromise or consensus building.” (p. 509)

This hurt him politically many times throughout his life. As we mentioned last week, he did not value the opinions of common people, but felt the federal government should dictate right and wrong to them. “This may have been why (James) Madison was so adamant that ‘Hamilton never could have got in’ as president.” (p. 509)

Hamilton wore his emotions on his sleeve. Often without decorum, he shared his opinions – in private letters or public pamphlets – that garnered plenty of attention. He had many detractors because of this.

“Hamilton was incapable of a wise silence.” (p. 534)

He frequently felt the need to defend his honor, even when his closest friends told him he didn’t need to do that. He wrote two pamphlets that severely damaged his reputation while he lived, one defending himself over a one-year affair he had with a married woman who was blackmailing him while he was treasury secretary, and the other criticizing then-president John Adams over their political differences (even though they were both members of the Federalist party).

“Rather than make peace with John Adams, he was ready, if necessary, to blow up the Federalist party and let Jefferson become president.” (p. 615)

While Hamilton held strong opinions on many subjects, including moral judgments, often to his own detriment, his views on religion softened in his later years, as evidenced by his deathbed pleas for holy communion.

Thank you, Bill. Now I want to read the book.

LikeLike